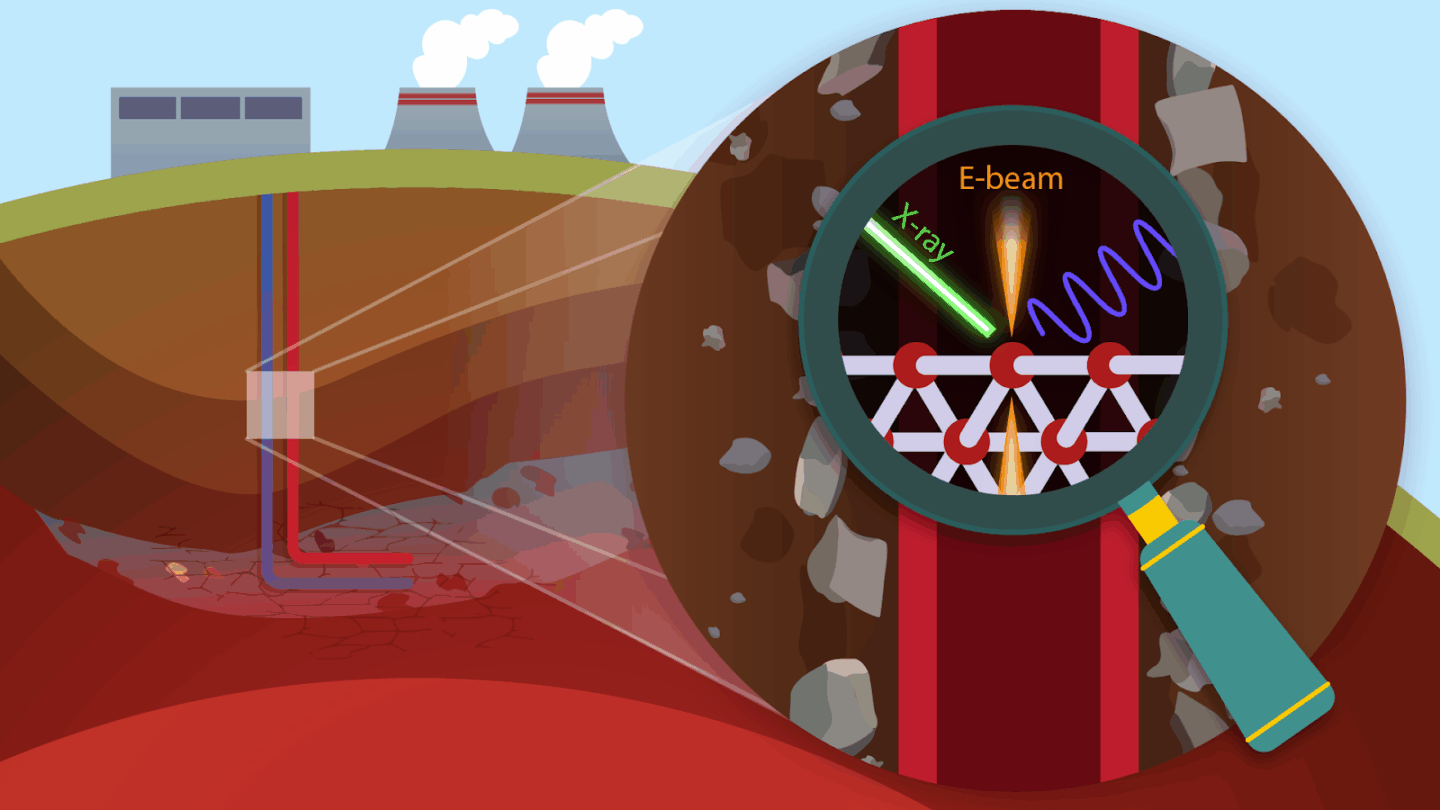

Enhanced geothermal systems technologies (EGS) create human-made reservoirs in Earth’s subsurface to bring heat to the surface for electricity. It’s challenging and expensive, however, to find materials that endure and function under the high temperatures within Earth’s core–as high as 572 degrees Fahrenheit–for decades. The sooner we identify materials suitable for building geothermal wells that can withstand these conditions, we’ll be closer to scaling geothermal energy as a reliable and affordable domestic energy source.

In collaboration with Senior Scientist Haimei Zheng from Berkeley Lab’s Materials Sciences Division and scientists from Brookhaven National Laboratory, EESA Research Scientist Chun Chang conducted a study, published in October in Science Advances, examining how a certain type of cement material transforms at extreme temperatures found in geothermal environments. Their finding that layers of the material shift under extreme heat is the first to document the cement behaving in such a way, and can help us understand how materials respond to harsh EGS conditions.

The team used an advanced transmission electron microscope (TEM) at Berkeley Lab’s Molecular Foundry that allows scientists to study materials at the nanoscale–where a single human hair is 75,000 nanometers thick. This demonstrates how the unique capabilities of national laboratory user facilities, combined with Berkeley Lab’s team science approach, drive solutions to real-world challenges.

Visualizing nanoscale details of material transformation

“Well cementation can cost up to 30% of the total geothermal well construction cost,” explained Chang. “By understanding the behavior and transformations of promising and affordable materials under geothermal conditions, we can improve well and reservoir engineering practices and effectively mitigate the potential impacts of material changes in these environments.”

Studying how materials respond to high temperatures thousands of feet underground is difficult, especially at the level of detail necessary to inform industry development. But creating similar conditions in a lab setting allows scientists to more easily gather detailed information on nanoscales to see how potential EGS reservoirs and well materials might respond to these conditions.

The team focused on cement made with gibbsite because it is strong, hardens quickly, and lasts longer, making it a good choice for tough environments like geothermal wells.

Implications for earth and materials sciences

The researchers combined in situ synchrotron X-ray and TEM to study how gibbsite transforms under heat. Using the Molecular Foundry’s transmission electron microscope, they captured nanoscale structural details by analyzing how electron beams scatter through the material, revealing properties like strain. This enabled them to create 2D videos showing the material’s dynamic behavior at temperatures up to 300 °C.

When testing the gibbsite material over several minutes under heating, the team observed rotational moiré patterns from twisting of two stacked gibbsite layers. Through detailed analysis of the pattern evolution, the team identified distinct ways the gibbsite responded to high temperature, including layer twisting and deformation. They then used AI neural network modeling to quantify their laboratory observations.

“We were able to show that high temperatures create molecular-level deformation in the gibbsite-based cement,” explained Chang. “This is important information to help guide the development of geothermal well materials that can tolerate the high temperatures deep within Earth’s core. But we still need to show what this twisting means for potential use in EGS well development.”

This Berkeley Lab research offers new insights into how materials behave under high temperatures, and thus may have broad implications for both earth and material sciences.