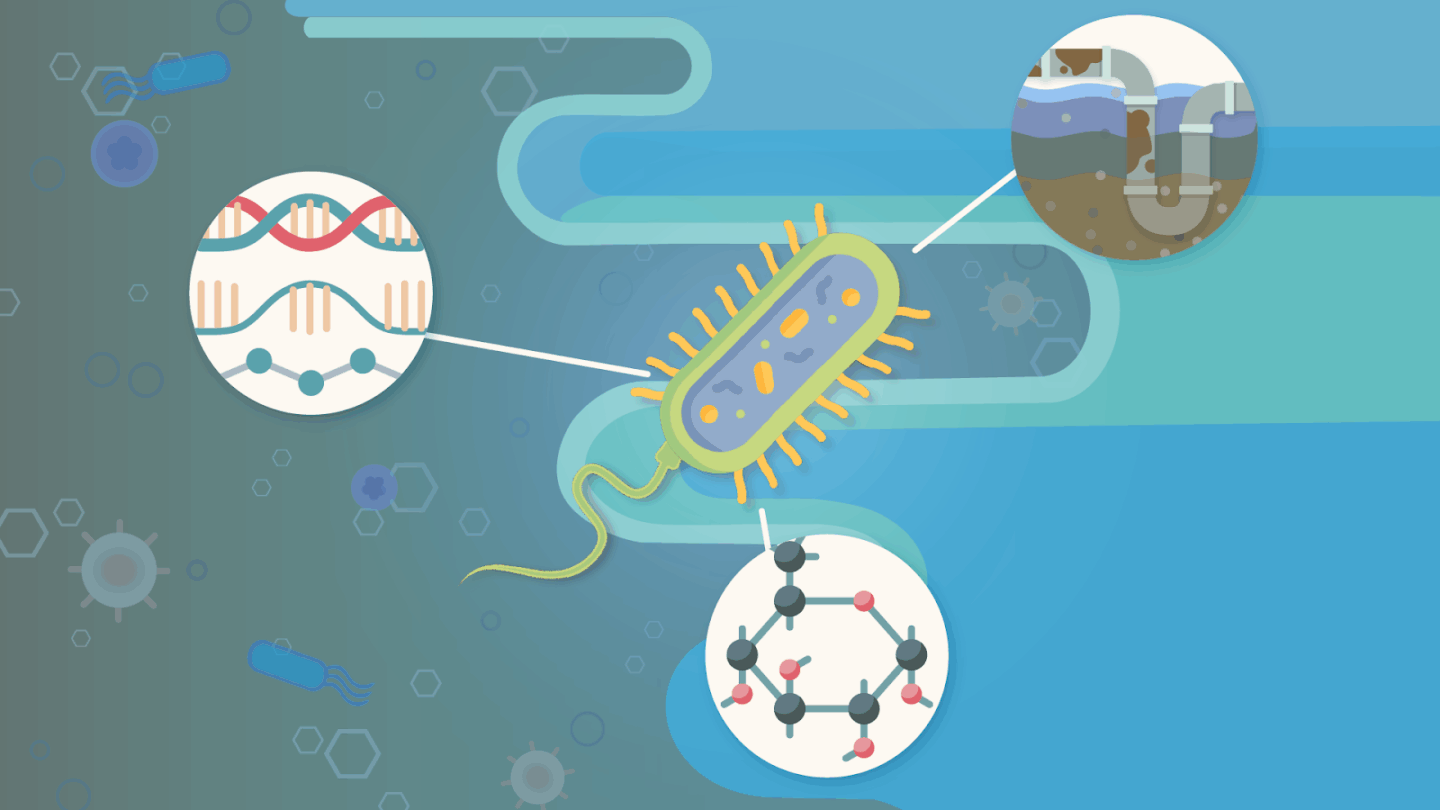

Extracting oil and gas from beneath Earth’s surface involves a lot of water. Produced water (PW), which exists naturally underground and is pumped to the surface during the oil and gas production process, is contaminated with salts, industrial chemicals, and hydrocarbons–the building blocks of oil and natural gas. Only about 1% of the billions of gallons of PW are reused, and the rest is discarded. Earth and Environmental Sciences Area (EESA) scientists are trying to change that with the help of contamination clean-up experts: microbes.

A new paper published in Microbiology Spectrum describes a study that investigated the genes and traits of Iodidimonas, a group of bacteria known to be abundant and thriving in systems that treat PW. The team–led by EESA Scientist Romy Chakraborty, Postdoc Yuguo Yang, Postdoc Shwetha Acharya, and the Biosciences Area’s Environmental Genomics and Systems Biology Division Director Susannah Tringe–found that these microbes have specific genes that help them survive in salty, toxic environments, but surprisingly don’t directly break down hydrocarbons.

“Our findings indicate different types of bacteria involved in PW treatment might work together,” said Chakraborty. “Iodidimonas may not degrade hydrocarbons, but it may be an important type of microbe that balances other communities that do by breaking down byproducts and consuming other microbes.”

Breaking it down with bacteria

Microbes are experts at turning hydrocarbons into simpler, less harmful byproducts. By growing the microbes that break down a specific contaminant in a container called a bioreactor and then adding PW, the hardest part of the treatment process is done. The microbes take it from there, digesting the toxic compounds and releasing different molecules in the process. Then, different microbes digest those molecules, releasing other byproducts that another microbial community needs for food, survival, or function. This process continues until only simple, unharmful byproducts are left, such as water, nitrogen gas, and carbon dioxide.

As water demand continues to increase, but freshwater resources dwindle, scientists are trying to figure out how to reuse unconventional water sources like greywater, brackish water, and PW so that these resources can be recycled for agriculture and industry needs.

Previous research has found the bacteria used in this study, Iodidimonas, to be one of the most abundant and prevalent types of bacteria that appear in PW bioreactors. However, fewer studies have addressed why or how the bacteria are able to survive in these conditions, and what their role is in the PW treatment process. Scientists can use this in-depth understanding of how specific microbes actually do (or do not) break down hydrocarbons to optimize PW treatment.

Although, because of its specific metabolism type, the activity of Iodidimonas has also been known to corrode pipes.

“Are these microbes necessary, or are they just in PW by chance?” Yang questioned. “And since they corrode pipes, can we remove them? Or are they needed for the survival of other microbes that do break down hydrocarbons? These were also part of the questions that guided our study.”

Sampling, isolating, and sequencing Iodidimonas

The scientists took sludge samples at different time points from a PW membrane bioreactor, which uses a combination of microbes to break down contaminants and membranes to filter out solids. From three of these samples, they isolated different strains, or subtypes, of Iodidimonas, for further study. Researchers catalogued the different characteristics of the microbes (such as metabolism, cellular makeup, and growth conditions) and analyzed DNA to create a genetic blueprint, or genome, of each bacterial strain.

Just like human hair color or the ability to curl your tongue, certain functions and traits of microbes are dictated by specific genes. This data gives insight into relationships between genes and traits needed to understand how Iodidimonas survive in toxic environments and their role in breaking down hydrocarbons.

“There are nine total strains of Iodidimonas,” Yang said. “Before our study, only four strains had their full genomes publicly available. Now, our study has contributed full genome data for three more strains, making complete data for a total of seven strains available in a global microbial database.”

Survival and balance in toxic waters

The team found that Iodidimonas prefer salty, more oxygen-rich environments, and don’t rely on outgrowing other microbial communities to persist.

Genetic analysis showed that Iodidimonas has many genes that help it handle high concentrations of salt, heavy metals, harsh chemicals, and some carbon compounds, and that it forms biofilms–protective external slime layers–to help it survive. But despite living in PW environments, it doesn’t eat oil and gas compounds directly, and instead likely relies on the byproducts or remains from other microbes. This indicates Iodidimonas is still an important piece of the puzzle in the breakdown of PW by balancing other microbial community members.

“With a better understanding of the role that Iodidimonas play in PW environments, this study can inform better design of bioreactors through incorporation of microbes with similar genes or traits,” said Yang. “Our findings also emphasize the importance of microbial ‘teamwork’ in the treatment of PW, as some microbes are responsible for breaking down hydrocarbons, and others recycle byproducts and waste.”