A recent Berkeley Lab study analyzes shrinking snowpack patterns historically and into the future, and the implications of a low-to-no-snow future for western water management.

Snowpack is a major element of western water systems, acting as a vast natural reservoir of water, especially for regions that rely on snowmelt during dry seasons. This snowpack is already shrinking and is expected to diminish substantially in the next 35-60 years in the American West, but the potential to adapt to–or even avoid–a future with less snow does exist.

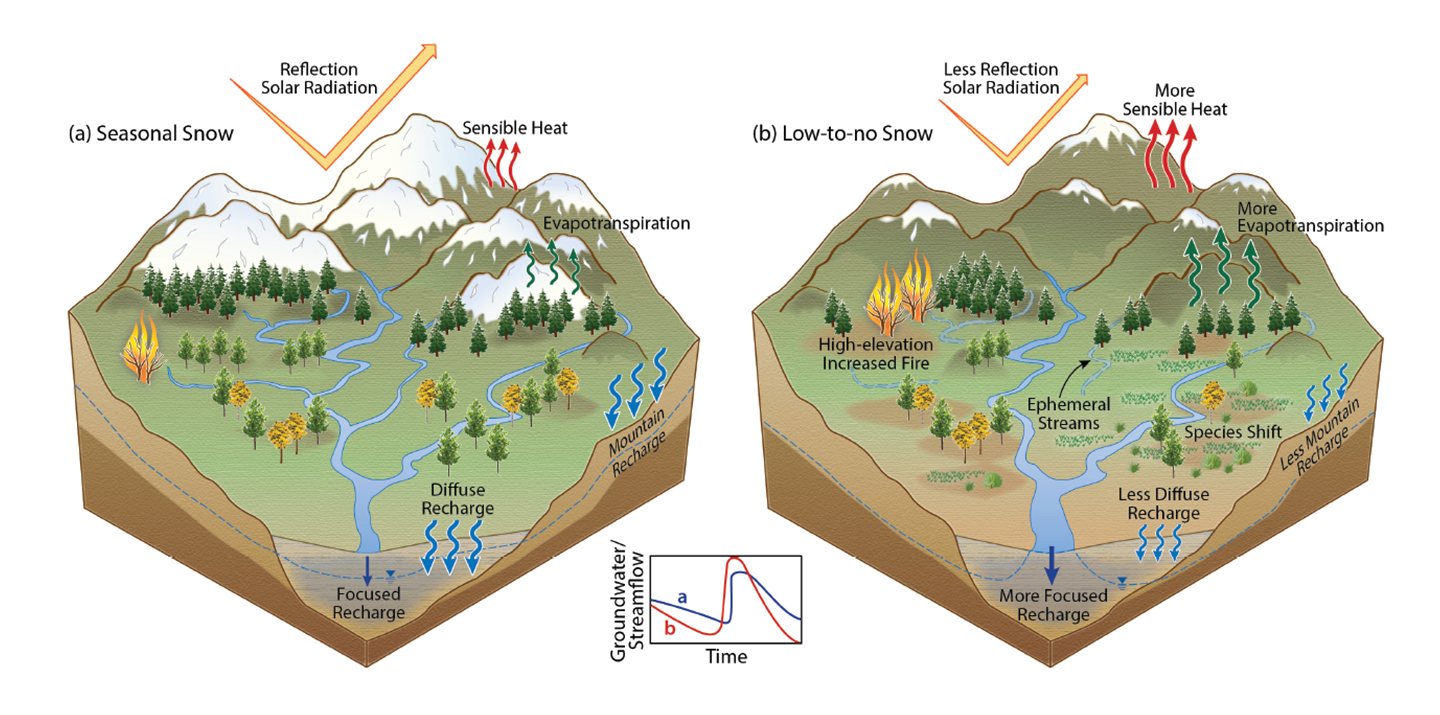

Mountains are often called Earth’s “water towers” because they capture, store, and release about 60% of Earth’s freshwater. This ecosystem service largely depends on seasonal mountain snowpack, specifically through spring and summer snowmelt. The water released during the snowmelt season is critical to buffer water supply, especially during dry seasons in the western U.S. when water demand for agriculture, municipal services, and ecosystem health and functioning is particularly high, yet precipitation is low.

Based on a synthesis of existing climate projections, researchers from the Earth and Environmental Sciences Area at Berkeley Lab have estimated that snowpack in the western United States may decrease 20-30% by the 2050’s and 40-60% in the 2100’s, especially if greenhouse gas emissions remain high. Their study defined “low snow” and “effectively no snow” conditions as when annual peak snowpack is below the 30th percentile of its historical peak and assesses the consecutive years that this condition is met.

One projection showed that California could experience “persistent low-to-no-snow” conditions, which occur when more than half of a mountain basin experiences low-to-no-snow for 10 consecutive years, by the 2060s. Other western regions could experience these conditions in the 2070s. This knowledge is key in providing a deadline to develop and implement climate adaptation strategies in anticipation of this low-to-no-snow future.

Because about 75% of the water resources in the West come from mountainous watersheds, decreasing snowpack could largely influence freshwater availability, and societies relying on this resource could face multi-billion dollars worth of risk. In addition to snow loss, a warming world will alter precipitation phase and timing which can further influence streamflow patterns due to earlier spring snowmelt and decreased recharge potential.

This brief is based on the paper, “A low-to-no-snow future and its impacts on water resources in the western United States,” published in the journal Nature Reviews Earth & Environment.

- About 75% of water resources in the western United States come from mountainous watersheds.

- In California, an average snowpack in April stores nearly double the amount of water as surface water reservoirs.

- Across the West, seasonal mountain snowpacks store about 200 cubic kilometers of freshwater every year – the equivalent of about 80 million Olympic-sized swimming pools.

- About 40 million people, a vast amount of agricultural land, and the majority of hydro-electric power plants in the western U.S. rely, at least partially, on streamflow that results from snowmelt.

Erica Siirila-Woodburn is an EESA research scientist whose research is focused on integrated groundwater-surface water hydrologic modeling, post-wildfire impacts on water supply, and the role of climate extremes on watershed hydrology.

Alan Rhoades is an EESA research scientist whose research is focused on the mountains of the western U.S. across long-term (hydroclimate) and short-term (hydrometeorological extremes) timescales.