Although more than half the world’s countries have committed to protecting at least 30% of land and oceans by 2030 in support of biodiversity, various questions emerge: Where and what type of land should be protected? How will new land protections impact carbon emissions and climate change, or the land needed for energy and food production? As a result, many decision makers are left questioning how to take action around protecting new land as they set their sights on achieving ambitious targets to preserve biodiversity in regions around the globe. New science tools can shed light on some of those questions.

A recent study led by climate scientists from the Department of Energy’s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab) aims to inform the discussion around how protecting additional land to meet conservation goals may impact land use (such as agricultural) and land cover (such as grass, water, or vegetation). The research is among the first to explore how potential pathways to achieve these bold targets affect agricultural expansion, and its findings suggest that meeting the 30% protection targets could lead to substantial regional shifts in land use and in some cases still fail to protect the world’s most biodiverse hotspots.

“It is important that we protect land if we want to stem additional ecosystem degradation,” said the paper’s lead author Alan Di Vittorio, a research scientist in Berkeley Lab’s Earth and Environmental Sciences Area. “But protecting land entails tradeoffs with other land uses and could have negative impacts on the agricultural sector, such as less land for bioenergy crops or less forest land for timber.”

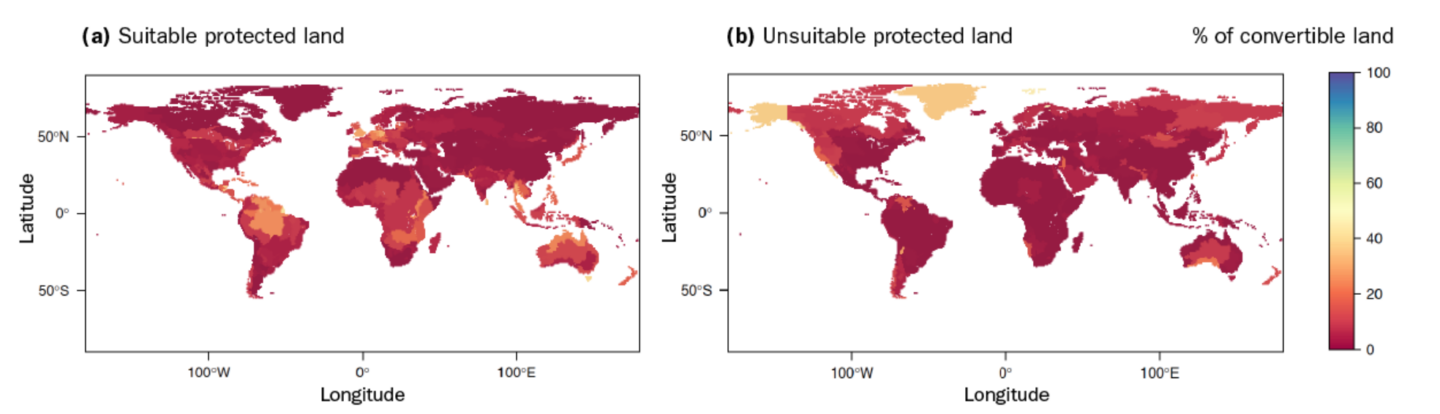

With biodiversity on the line, escalating food demands, and finite amounts of land available, the study explores the competing priorities that exist when selecting new lands for protection in order to minimize potential downsides for the agricultural sector and maximize progress toward well-defined conservation goals (such as clean water or wildlife habitat). Through a detailed analysis of a series of computer simulations, the researchers estimated the effects of approximately doubling currently protected land to meet the 30% protected land target. They incorporated new spatially explicit land availability data into their modeling to represent land that is suitable or unsuitable for agriculture; and protected, highly protected, or minimally protected. The study results indicate that detailed, region-specific land information is an important factor when selecting new lands for protection and estimating the potential impacts to agriculture of the resulting reduction in land availability.

One of the most notable findings is that the land used for growing crops for conversion into biofuels could be significantly impacted by the doubling of current protected areas. Under this scenario, the analysis showed a 10% global decrease in these bioenergy croplands to maintain food production, with that number climbing far higher in some regions (46% decrease in Russia and a 39% decrease in Canada). Some of the losses were partially offset elsewhere, such as in Northern South America where the analysis showed a 36% increase in bioenergy feedstock land.

The research also showed that for half of the 384 regions modeled, it would be possible to meet the 30% target by protecting just agriculturally unsuitable land, however this land may not coincide with one or more of the world’s 36 biodiversity hotspots. For example, the Northern Africa region could meet its 30% target by protecting only the desert, which contains few ecologically sensitive areas and thus has limited benefit to biodiversity. The study therefore illustrates that the uneven distribution of species across an area may have significant bearing when it comes to understanding and managing changes in land use, and how this impacts biodiversity.

Di Vittorio concludes, “Our study adds to the literature exploring how we can meet both environmental and human needs as countries around the world unite around the goal of protecting land for biodiversity.”

This research was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science.

# # #

Founded in 1931 on the belief that the biggest scientific challenges are best addressed by teams, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and its scientists have been recognized with 16 Nobel Prizes. Today, Berkeley Lab researchers develop sustainable energy and environmental solutions, create useful new materials, advance the frontiers of computing, and probe the mysteries of life, matter, and the universe. Scientists from around the world rely on the Lab’s facilities for their own discovery science. Berkeley Lab is a multiprogram national laboratory, managed by the University of California for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science.

DOE’s Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit energy.gov/science.